Preparing for the Inevitable: Building for the Hypothetical

Only a year after the U.S. dropped the Fat Man and Little Boy bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviets had tested their own version of "the bomb". Anxieties surrounding the possibility of Nuclear War on American soil led to several discourses that transformed possibility into inevitability. The resulting formation of both the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) under President Truman, later replaced by the Office of Civil Defense Mobilization in 1958, brought the government into formulating plans to would contain the destruction of nuclear war. As the discussion of preparedness began to encroach upon on the question of weather "To dig, or not to dig", new approaches to planning evacuations and protective structures had to rely on events that were only loosely analogous.

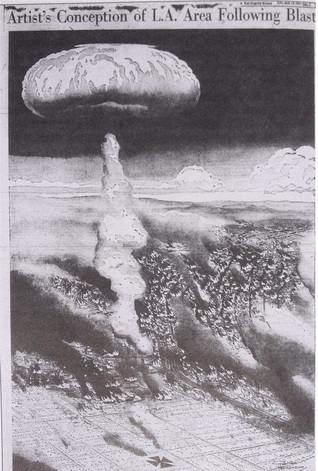

Having never experienced such an event as a nuclear detonation, natural disasters and tests that illustrated the bomb's destructive power became essential to imagining the effects on structures in cities across the country. While the discussion of "nature" grounded the imagined in an understandable metaphor, it also contributed to the belief of the inevitability of nuclear war. While bomb testing could supply a rough idea of destructive potential, results had to be applied to densely populated and over-built cities. In major cities, newspapers circulated imagery that contributed to communicating this theoretical understanding in more of the hypothetical "What if" scenarios.

Having never experienced such an event as a nuclear detonation, natural disasters and tests that illustrated the bomb's destructive power became essential to imagining the effects on structures in cities across the country. While the discussion of "nature" grounded the imagined in an understandable metaphor, it also contributed to the belief of the inevitability of nuclear war. While bomb testing could supply a rough idea of destructive potential, results had to be applied to densely populated and over-built cities. In major cities, newspapers circulated imagery that contributed to communicating this theoretical understanding in more of the hypothetical "What if" scenarios.

The Nuclear Family: Private Fallout Shelters

"The Foxhole"

Assuming that major cities would be targets for bombing, early efforts prioritized moving defense industry workers out of the city and into suburbs away from the devastation of an attack. Los Angeles itself had become the largest defense aerospace complex in the world. Companies, including Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, Northrop, Hughes, Rockwell, Litton and TRW, all contributed to L.A.'s "other industry". While the movement of large numbers of workers to adjacent cities surrounding Los Angeles was strategic, "racist real estate practices, racial covenants, and organized white resistance often restricted non-white populations to older, inner-city neighborhoods..." (M). As a result, the image of suburban development took on a very specific form.

|

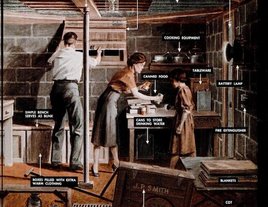

While suburbanization would successfully evacuate many from the city, suburban areas provided the ideal setting for backyard or basement shelters. When the FCDM was replaced by the OCDM, the new line became a "do it yourself" approach to containment and preparedness. Congressional resistance to paying for a comprehensive program, and a general belief following from previous wars in the limited involvement in government produced a "gospel of Self Help". Although the government could not guarantee the survival of every citizen, the "Self Help" approach placed responsibility on every person, and was essential in producing a reliance on government agencies to produce information believed to be essential to shelter design. Often, they went as far as to designate roles for each member of the family, which were largely based on the conventional structure of the 1950s.

|

|

|

Although the numerous pamphlets and films produced by civil defense programs sought to inform citizens on how to protect themselves and their families, little was known about the full effects of radioactive fallout. In their initial form, basements and simple structures (like the "Foxhole" above) were converted into bunkers where the family could survive the effects of the initial blast, with time ranging from days to weeks. As more was learned about fallout, families could be expected to live underground for months or years (given a Doomsday-like scenario). Government offices and private contractors began catering to a white middle-class image of suburban life as later designs of family shelters promised to minimize the effects of a nuclear war on the daily lives of individuals. With a sense of security and comfort lacking in earlier models, occupants could continue to live their lives underground just as they would above.

|

Although few shelters were actually built, those that were often included a certain amount of secrecy. Shelter owners were often plagued by the thought of unwanted people showing up, and in need of supplies. Even officials from surrounding cities, such as Las Vegas and those in Riverside county, feared an influx of "refugees fleeing H-bombed Los Angeles". As a result new questions of morality began to be raised on the hypothetical scenarios that could occur with the inevitable bombing. Even today, as the prospect of Armageddon looms in the imagination, shelter contractors such as Atlas Survival Shelters advertise that "Keeping your shelter secret is our #1 concern".