On the Surface: From the Glass Box to the Bunker

As Civil Defense officials promoted a "Self Help" approach to preparedness at home, the privatization of shelters not only raised concerns for morality, it also transformed the home-made shelter into an industry that promised a continued lifestyle in the face of nuclear war. As barricaded basements turned into underground replicas of homes, the divide between the family shelter and the bunker, first introduced by Civil Defense programs, continued to increase. However, just as below began to resemble above, architects designing public shelters followed a sense of functionalism that moved toward a bunker style. On the surface, combined elements of bunker architecture and modernist designs offered citizens greater comfort in their movement throughout the city, even if such elements were only psychologically reassuring. Greater emphasis was placed on buildings that could not only survive the blast of an atomic bomb, but offered protection from fallout. The result was that "above began to resemble below" ...As new architecture stressed functionality, 1950's corporate modernism's glass structure gave way to a windowless mass of concrete fortification.

|

In an attempt to control the language associated with building, the Office of Civil Defense attempted to coin a term for a set of strategies for building specifically for the prevention of fallout, which was termed "Slanting". While these strategies ranged in execution, most can be seen as using both "mass and geometry". Unlike private shelters, public shelters were also symbols of society, and as such could not be completely buried.

Using elements of Modernist architecture, like clerestories, fenestration could allow light in without the exposing people in public shelters to fallout. Likewise, by designing entrances to buildings at an angle in relation to hallways, fallout reaching the shelter within the building could be minimized. In addition to massive walls with minimal glazing, entrances could be shielded by massive walls running the face of the building. |

Above: Concrete walls of the shelter are reenforced by planters to give greater mass. Windows above permit light without the effects of fallout on the horizontal plane.

Below: Fallout could be stopped by designing curves and bends into the building. |

Public Shelters/Private Buildings: L.A.'s City National Bank Building

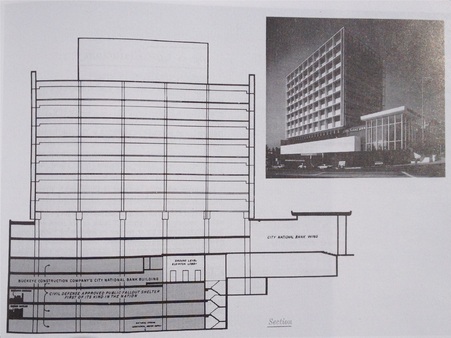

The City National Bank Building, designed by Austrian emigre Victor Gruen, was "the nation's first privately sponsored Civil Defense fallout shelter". Serving as a public shelter, built to house 4,000 people, the building represents the altruism of its owners who initiated the project and purchased their own supplies. It also reflects the public sense of civilian duty promoted by the government. After its dedication in 1961, the building and its owners, received recognition from Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and President John F. Kennedy himself.

The building anticipated aspects of bunker architecture, and demonstrated that fallout shelters could be built using extensive areas of fenestration typical of 1950s corporate modernism. Its glass pavilion is shielded from the street by a twelve-foot-high wall clad in polished granite, which was itself capped by two more blank horizontal planes at the mezzanine level. The combined planes offered excellent protection from fallout and other potential effects. Using concrete panels glazing was reduced by half in each square of the facade grid, a basic design for slanted buildings.

The building anticipated aspects of bunker architecture, and demonstrated that fallout shelters could be built using extensive areas of fenestration typical of 1950s corporate modernism. Its glass pavilion is shielded from the street by a twelve-foot-high wall clad in polished granite, which was itself capped by two more blank horizontal planes at the mezzanine level. The combined planes offered excellent protection from fallout and other potential effects. Using concrete panels glazing was reduced by half in each square of the facade grid, a basic design for slanted buildings.

An Emerging "Style"

Although the term "slanting" never became an official architectural term, the strategies themselves became a part of the bunker's movement to the surface. While many architects designed buildings with protection in mind, some used the windowless bunker as an ideal. Many schools, fire stations and government buildings built during this era show some kind of thinking of civil defense in mind. However, buildings in most major cities show varying use of the aesthetic of protection, and the massiveness of the bunkers influence.

The AT&T Switching Center, completed in 1961, is part of the AT&T Madison Complex Tandem Office. It is a 17-story skyscraper located at 420 South Grand Avenue. With its microwave tower, it is the 29th tallest building in Los Angeles. The father and son architectural team John B. Parkinson and Donald D. Parkinson, are responsible for several architectural marvels throughout the city, which include the L.A. Memorial Coliseum and Union Station. The microwave tower was used until 1993, connecting the 213 area code to local and long distance locations. As the 1980s brought about deregulation, Pacific Bell banned competitors from their central switching station leading long distance carrier MCI to mount its own microwave station on the roof of One Wilshire. However, the evolution of fiber optics eventually contributed to the obsolescence of such towers. Today, the buildings minimal glazing and imposing mass represents an almost complete subscription to the opaqueness of the bunker style-- the antithesis of the modernist glass structure.

The AT&T Switching Center, completed in 1961, is part of the AT&T Madison Complex Tandem Office. It is a 17-story skyscraper located at 420 South Grand Avenue. With its microwave tower, it is the 29th tallest building in Los Angeles. The father and son architectural team John B. Parkinson and Donald D. Parkinson, are responsible for several architectural marvels throughout the city, which include the L.A. Memorial Coliseum and Union Station. The microwave tower was used until 1993, connecting the 213 area code to local and long distance locations. As the 1980s brought about deregulation, Pacific Bell banned competitors from their central switching station leading long distance carrier MCI to mount its own microwave station on the roof of One Wilshire. However, the evolution of fiber optics eventually contributed to the obsolescence of such towers. Today, the buildings minimal glazing and imposing mass represents an almost complete subscription to the opaqueness of the bunker style-- the antithesis of the modernist glass structure.